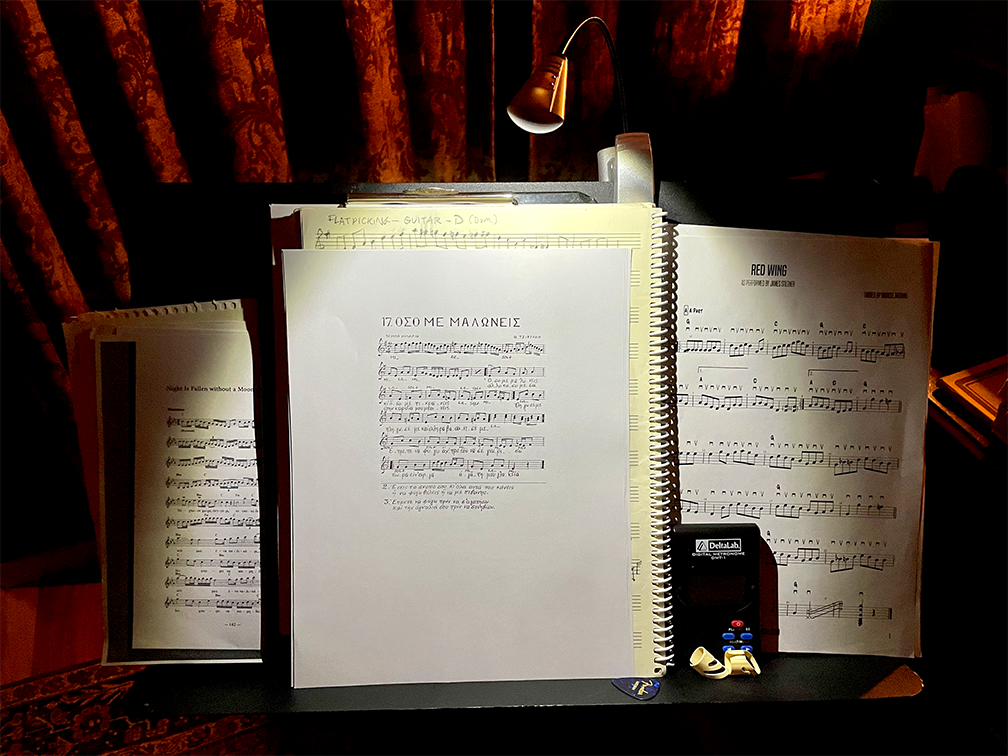

ΌΣΟ ΜΕ ΜΑΛΏΝΕΙΣ is the song — my first rembetika to learn instrumentally on guitar. The part I’m working on is normally on bouzouki (and other instruments, e.g. accordion and violin). I will learn at least a dozen of these bouzouki melodies on guitar, perhaps many more, by next spring, when I’ll be in Athens and plan to buy a bouzouki of my own.

I have read the part from sheet music, but the recording is the real guide. Rembetika is like jazz or bluegrass in this sense — the melodies transcribed in books rarely tell the whole story. Often the signature parts of a tune, as devoted practitioners play it, may be those from an authoritative recording of an early player, or from direct person-to-person transmission, rather than from a supposedly-canonical transcription.

My approach to learning has some structure from years of exploration of many types of music. I’m able to memorize the piece fairly quickly. I’ve always been more a memorizer than sight-reader — I learned to play guitar primarily by ear from blues and rock records, and by memorizing classical pieces slowly measure-by-measure. I use the metronome at a fairly slow click to get those little thirty-second note figures (which aren’t even in the score) to hit right.

There’s a platitude that music is a ‘universal language’, which is somewhat supported by the way musical discipline can transfer to learning music of different cultures, and also in the way musicians from different cultures can collaborate. I recently saw the 50th anniversary tour of Shakti, which was a definitive influence on me when I discovered their record A Handful of Beauty in my teens, and a beautiful example of different cultural traditions intersecting generatively.

But this universal language sentiment is also misleading. Each developed craft of music — like rembetika, jazz, blues, bluegrass, punk rock, Hindustani music or Balinese opera or Gregorian chant — is its own language. And to devote yourself to that music means not just to imitate its surface, but to immerse and learn that language. In this sense I know that my adventure here is just at its inception. Learning my first rembetika is like learning the first verb conjugations and sentences of a new language, but it will take many hours of both conscious intention and unconscious intuition before I experience that click, that organic soul-synthesis of really being able to convey rembetika as an utterance — which is what art is. Not an object, not a surface, but a cooperation between psyche and psyche, and between individual and community.

And this reminds me, again, of the things AI can’t do. You might feed into a cleverly programmed neural net all available rembetika song melodies, and it could train on this data and, possibly, produce a series of reasonably “convincing” original rembetika melodies, likely with some weird and unexpected innovations. But in doing so, the process is significantly different from human language learning or human artistic creation. Rather than a soul driven by a need or desire to communicate with another soul, to participate in a conscious community, we have an engineered automation mechanism capable of very sophisticated interpolation of variations and continuities in surface-structural elements of the data from musical ‘objects’. Community does not matter, the intention or desire of a soul does not matter, the stories of the originators does not matter, the adventure of individual discovery does not matter; only the decomposition of and manipulation of surfaces matter. And so, the areas where AI will have the most impact are those where, even prior to AI, the decomposition and manipulation of surfaces were primary — in consumerism, in digital media (abstracted away from in-person communities), in demographics-driven business and economics, in mass politics, in conspiracy theories and other facile mis-informational addictions, in domains where prolific objectification mechanisms prepared the way and shallowed the mind. I think there’s a real chasm of choice opening up here, for artists. The consumerist models for art, which were already avenues of escalating impersonal commodification (evidence: the very phrase “content creator”), are burst bubbles for us with the rise of AI. Community is the new frontier, and was always the real garden to be cultivated. But enough, for now, on the empire of distraction…

I’m excited for this beautiful adventure through the different world of these songs. Every hour doing something you love, and connecting with human utterance and art, is magic. Below is the recording that’s guiding me for this one. It features Πάνος Γαβαλάς, Βασίλης Τσιτάνης and Μπέμπα Φινέτη. (That’s Pavos Gavalas, Vasilis Tsitsanis, and Beba Finoti, for those on the newfangled Latin alphabet).